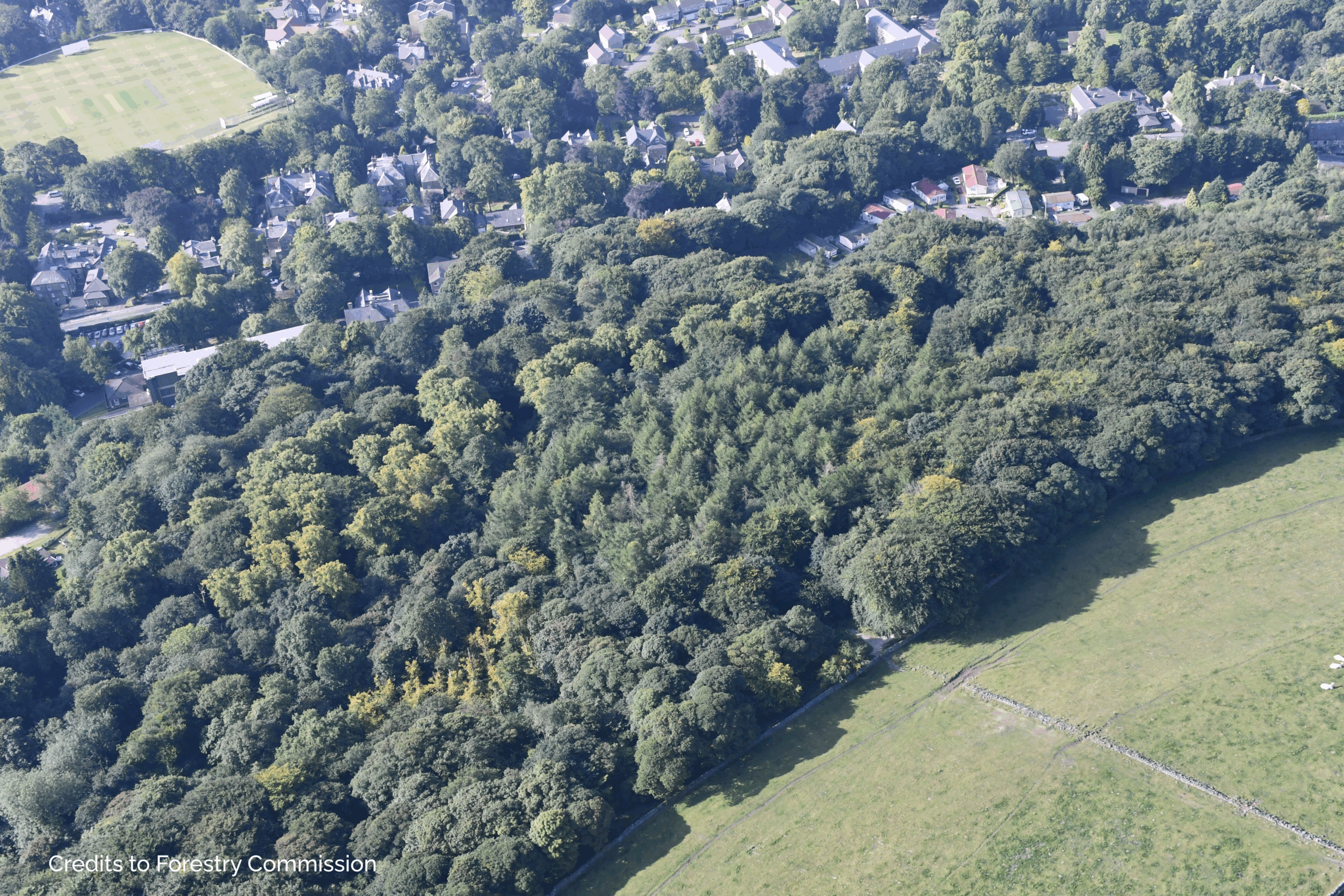

Corbar Woods: Tree Felling to control Larch Disease and protect woodland health

Thursday 6th November 2025

Buxton Civic Association (BCA) has confirmed the presence of Phytophthora ramorum — commonly known as larch disease — in Corbar Woods, Buxton. Following confirmation of infection, the Forestry Commission has issued a Statutory Plant Health Notice (SPHN) requiring BCA, as the landowner, to take immediate action to prevent further spread of the disease.

This means that all larch trees must be felled, and all rhododendron removed from Corbar Woods. The work will be carried out by qualified contractors under the supervision of BCA’s professional Woodland Team.

Dave Green, Chief Executive of BCA, said:

“This is sad news for everyone who loves Corbar Woods, but these measures are essential to protect the wider landscape and neighbouring woodlands. By taking decisive action now, we can help prevent the spread of infection and give the woodland the best possible chance to recover and thrive.”

During the felling operations, some areas of the woodland and public footpaths will need to be temporarily closed for safety. BCA is asking visitors to follow all on-site signs and instructions to protect themselves, contractors, and the woodland environment. Updates on closures and progress will be available on BCA’s website and social media channels.

What is Phytophthora ramorum?

Phytophthora ramorum is a water-borne mould that attacks the bark and foliage of trees and shrubs. It can infect more than 150 plant species, with larch, rhododendron, and sweet chestnut particularly vulnerable. The only way to contain the disease is to fell infected trees and remove potential hosts to eliminate sources of spores.

Restoring and replanting the woodland

Once felling is complete, BCA will begin a programme of restoration and replanting. Areas will be allowed to naturally regenerate, supported by carefully planned replanting with native species such as oak, birch, hazel, yew, holly, guelder rose, elder, and hawthorn — trees that are more resilient to climate change and future disease.

Where possible, timber from the felled trees will be reused for conservation projects across BCA’s nine Buxton woodlands, including fencing, habitat creation, and woodland infrastructure.

Harriet Saltis, BCA Woodland Manager, added:

“While the loss of larch and rhododendron will change the appearance of Corbar Woods in the short term, it also offers an opportunity to create a stronger, healthier woodland that will support more wildlife and remain a treasured space for the community for generations to come.”

How can you help?

Although P. ramorum poses no risk to people or animals, it spreads easily through soil, mud, and plant material. Visitors can help prevent further spread by:

- Cleaning boots and paws before leaving the woodland.

- Washing footwear (ideally with disinfectant) before visiting another site.

- Staying on marked paths and keeping dogs on leads.

- Leaving all wood, leaves, and plant material where they are.

Supporting BCA’s charitable work

Responding to this outbreak represents a significant and unexpected cost for BCA, covering felling, timber removal, restoration, and replanting. Community support is vital.

You can help by:

- Donating to BCA

- Becoming a BCA member to support conservation across Buxton’s woodlands and Buxton’s heritage.

- Volunteering with BCA.

Every contribution helps conserve and enhance Buxton’s woodlands for the future.

Read more about Corbar Woods Larch Disease and Woodland Conservation here